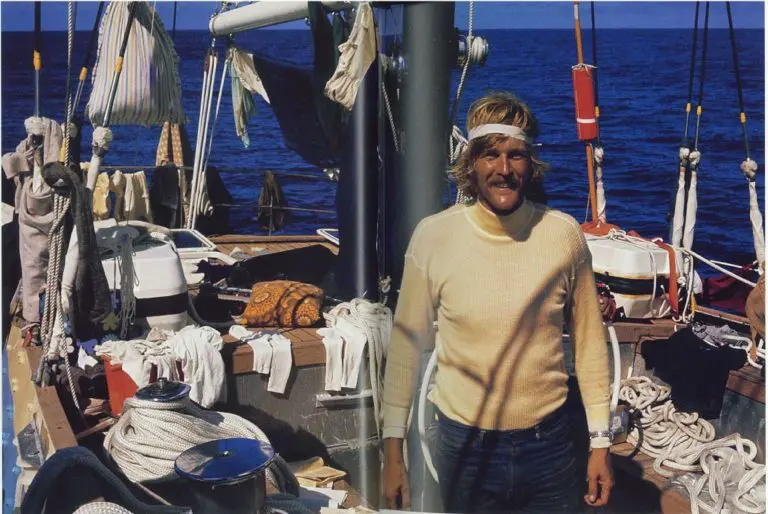

“The decks hadn’t been caulked so they leaked, forcing one crew member to sleep under a large black umbrella in his bunk. It was a real learning period in those days.”

– Sir Peter Blake

All this experience stood Blake in good stead for a berth in the first round the world race and he joined Leslie Williams’ crew on Burton Cutter. Ill-prepared, Burton Cutter’s campaign was doomed from the outset.

Seized by a passion for yachts and the sea, it was inevitable that Peter Blake would be an early and ardent disciple of this event. It blended his love of yachts and racing with an equal love of adventure and distant journeys.

After winning the 1967-68 New Zealand Junior Offshore Group (JOG) championship in Bandit, the 23ft racing yacht he built in the family garden, Blake was keen to see the world. He sold Bandit and used the money to pay for a flight to England, following a classic New Zealand rite of passage known colloquially as the Big OE (overseas experience). Inevitably, he gravitated to the sailing scene and was soon crewing on all sorts of yachts on the European racing circuit.

In 1971, he secured a position as watch leader on the yacht Ocean Spirit, which won the inaugural Cape Town to Rio de Janeiro Race. On the way down the Atlantic to the start of the race, Ocean Spirit struck a sandbank off the notorious coast of Namibia and the crew was lucky to escape with the yacht intact and nobody injured.

All this experience stood Blake in good stead for a berth in the first round the world race and he joined Leslie Williams’ crew on Burton Cutter. Ill-prepared, Burton Cutter’s campaign was doomed from the outset.

Sailing out to the start line off Portsmouth, the crew was still desperately trying to complete the interior, hammering makeshift bunks into place. The helmsman’s seat was a cardboard beer carton, which promptly disintegrated as soon as it got wet.

There was nowhere to stow provisions, so they were bundled up into a tennis net, lashed as a hammock down the length of the saloon. Later, the provisions were stowed in the bilge, but the toilet system had been improperly installed. Everything had to be thrown away when it was discovered that raw sewage was being pumped into the bilges.

The decks had not been caulked, so water poured through into the cabin, forcing the crew to find shelter where they could. One was fortunate enough to have a large black umbrella of the type favoured by London businessmen and slept under that.

After leading the 17-strong fleet into Cape Town at the finish of the first leg, the yacht was forced to withdraw from the race during the second leg to Sydney after suffering structural damage in a Southern Ocean gale. The interior was still not finished, and the crew was able to use bits of timber intended for interior furnishing or bulkheads to shore up the badly damaged yacht. Burton Cutter limped back to South Africa and then later cruised across the Atlantic to Rio, where she joined the race again for the last leg back to England.

Blake put it all down to a “learning period” and indeed his later obsession with planning and meticulous attention to detail might well have found some of its roots in the chaos of that first Whitbread attempt.